To celebrate Mother’s Day: Mrs Bennet – the mother we love to hate

Every film or TV series of a novel set in the past recreates the novel through the lens of its own time.

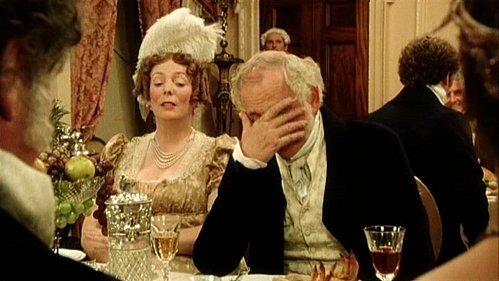

Hence all these different Mrs Bennets. In the earlier adaptations she was strident, silly and money-grabbing, the coldness between her and Mr Bennet easily understandable – his cool rationality set against her hypochondria and hysteria.

These early incarnations of Mrs Bennet were misogynist creations, close to the mother-in-law stereotype, the Hyacinth Bouquet figure, the classic ridiculous middle-aged woman, beloved of sit-coms and old-school stand-ups, with her risible clinging to her lost youth, her faded looks, her ‘nerves’ and her slow brains, easily outwitted by her smart-arse husband and daughters (see…. this blog post…for my deconstruction of Mr Bennet – no more Mr Nice Guy).

Then in the more recent adaptations – the 2005 film, and also Lost in Austen – the reconstruction sets in. A feminist take on history is evident in the characterisation – Mrs Bennet’s venality and obsession with getting her daughters married is now to be sympathised with from a 21st-century standpoint: after all, what choices did women have in those benighted times?

Brenda Blethyn has some of the silliness, but she is also earthy, fully conscious of the social position of women, and surprisingly has a full sexual relationship with her husband, and even gets some love from Lizzy.

In the highly knowing Lost in Austen, a time-travel take on the novel, we get the most powerful, the most politically aware, and definitely the most genuinely sexy Mrs Bennet in the storming Alex Kingston

.

But what of Jane Austen herself? Jane Austen was not sentimental, she was not a feminist and in my view she wasn’t really romantic, even though her books are all love stories that end happily ever after.

All the characters, even the romantic leads, are seen through her piercing eye. She is interested in the lives of her female characters but she has no sympathy to spare for Mrs Bennet and her fate. In fact, women of a certain age often suffer badly from Austen’s sharp satire: Miss Bates in Emma, Mrs Musgrove in Persuasion with her “large fat sighings” (over the death of her son mind you – that’s how sympathetic Jane Austen was).

Despite the prince/pauper match-up of Elizabeth and Darcy, Jane Austen does not question the structure of social class of her time. She doesn’t pity Mrs Bennet’s dilemma and possible fate, she simply creates a believable caricature and skewers her with pithy dismissive remarks. (“She was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper. When she was discontented, she fancied herself nervous. The business of her life was to get her daughters married; its solace was visiting and news.”)

The Mrs Bennet of the book is not a struggling realist, she is not a devoted mother or a sexually active wife: she is a caricature – she is vapid, empty and cruel, a neglectful mother, narcissistic, irresponsible, hypocritical and – well, just stupid.

I can understand why recent adaptors have wanted to flesh Mrs Bennet out: mothers today have careers, incomes, we read books, we even read Jane Austen. Middle-aged women are bound to be a big chunk of the audience for any Pride and Prejudice adaptation, and middle-aged women today do not care to see ourselves depicted as silly, greedy and hysterical. Also, in our post-Freudian world, we are all interested in motivation, in why people are the way they are. In my Mary Bennet sequel, I took an even more caricatured character and decided to turn her into someone real. And of course my novel is informed by my contemporary understanding of and obsession with psychology and child development.

It doesn’t ultimately matter whether the adaptations are true to the book: in fact, they can’t be. The context in which Austen lived and thought is almost completely foreign to us now. The wonderful scene in Lost in Austen, when Mr Darcy suddenly finds himself in modern Piccadilly Circus gives a sense of how far apart our societies are, despite some superficial similarities. (I wish there was a pic that showed the shock on his face)

Despite my purist tendencies, I pretty much love all the P&P adaptations, including P&P and Zombies, though I can probably dispense with Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier. I look forward to what the adaptors of the 2020s come up with. After all –